Aerial view of São Jorge with the westernmost headland of Ponta dos Rosais in the foreground. (© José Luís Ávila Silveira/Pedro Noronha de Costa)

“After another seven days, a fire exploded in the vicinity of the parish of Santo Amaro, where it opened two mouths of fire, such as two great ravines of fluid material, and with such force that on the second day, we encountered more than a moio of fields of lava in the direction of the homes, forcing the people to flight; the vicar, Rev. Amaro Pereira de Lemos, lost his senses and his sister D. Anna Maria de Lemos went crazy.“

(Father João Ignácio da Silveira, May 1808)

Painting of São Jorge seen from the island of Faial during the 1808 eruption, showing the eruptive places and images of curling pyroclastic flows descending the cliffs of Manadas. Watercolour at the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, Lisbon, Portugal.

THE ISLAND – Ilha de São Jorge

Ilha de São Jorge, in the Central Azores group, lies just 19 km north of the island of Pico and is the fourth largest of the archipelago. It has a strangely elongated shape, rather like a giant letter opener – while it is 55 km long its greatest width is less than 7 km from the N to the S coast. Its highest point is Pico da Esperança at 1053 m.

Ilha de São Jorge, in the Central Azores group, lies just 19 km north of the island of Pico and is the fourth largest of the archipelago. It has a strangely elongated shape, rather like a giant letter opener – while it is 55 km long its greatest width is less than 7 km from the N to the S coast. Its highest point is Pico da Esperança at 1053 m.

Its coast is steep, almost vertical in places. The most impressive cliffs can be found along the northern coast, where they reach heights of 480 m. At the bottom of the cliffs small coastal flat areas called fajãs have been created by land slide deposits and lava deltas. These are where most of the residents live in small villages around the coast. Although, after the devastating earthquake of 1980, most of the fajãs were abandoned and only the safest and best accessible ones are still inhabited. The main municipalities of São Jorge are the small towns Velas, Calheta and Topo.

São Jorge’s natural beauty makes a long list of reasons to visit: dark mountain ranges, volcanic cones & rugged lavas, checker board tilled fields, the picturesque fajãs, verdant bird-inhabited islets, natural bridges, arches & grottoes, striking waterfalls & streaming rivers, green pastures & wild flowers, and vineyards & orchards growing atop fertile flatlands.

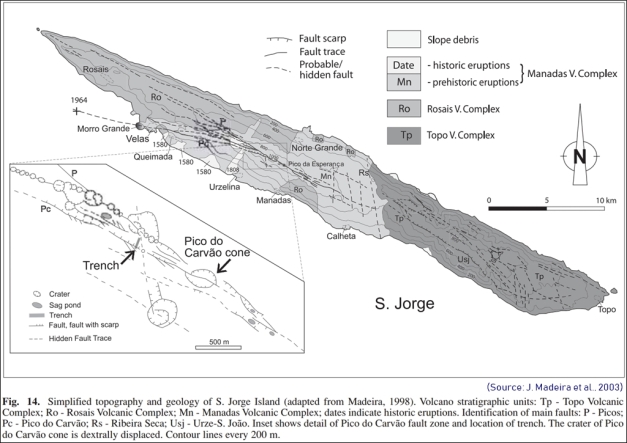

The volcanism that built the Azorean islands and submarine volcanoes is caused by tectonic processes (see agimarc’s post “Azores part 2 – Tectonics” for details). It is a result of the rifting crust that causes widespread active faulting in the surrounding seafloor as well as in the islands themselves. São Jorge sits on the São Jorge Fault which extends NW-SE. This fault lies in between and parallel to the Faial-Pico Fracture Zone in the S and the main Terceira Rift to the N.

The majority of early subaerial eruptions were of Strombolian and Hawaiian styles, producing basaltic scoria and lava flows. As with the other Azores islands, São Jorge is entirely built up of these volcanic rocks. The lavas erupted from a large fissure that had opened by the stretching processes along the fault. Massive amounts of lava piled up on the sea floor, until they finally surfaced as an island. Over time this fissure produced an over 50 km long line of ~200 monogenetic cones and their associated lava flows.

View along the “spine” in the central part of São Jorge were many of the more recent monogenetic cones are still visible. (Screenshot from video by Lion Manuel on YT)

Very nice drone video of São Jorge on YT, by Lion Manuel:

Looking closer at the island’s map one can see that a whole bunch of local and regional faults are responsible for its present geology. Two main normal WNW-ESE fault zones dominate the younger western part of the island: the Picos and the Pico do Carvão fault zones. The Picos fault is marked by the alignment of cones on the crest. The Pico do Carvão Fault shows a continuous scarp extending to Pico do Carvão crater on one end. To the west it extends to the shore and probably further into the sea to an assumed 1964 submarine eruption site.

There have been two strong earthquakes in the past: one M 7.4 in 1757 and one M 7.2 in 1980. Both caused heavy destruction in the eastern half of the island. With 1000 fatalities in 1757 a fifth of the population died, while in 1980 a few tens of people lost their lives. Pico do Carvão fault activity is also the source of recent volcanism on São Jorge.

Three volcanic complexes

Ilhéu do Topo off the eastern tip of São Jorge might have been the first volcanic cone (or one of the first) that peeked out above sea level when the fissure eruptions built this submarine mountain range. It is now completely flat, eroded by the sea and winds, and will be the first to disappear into the rock cycle again. (© Jessie, via Jessie On a Journey)

1. Volcanism began in the east, the early lavas of São Jorge are alkali-basalts of ~1.3 Ma. The Topo Volcanic Complex (SE) consists mainly of stacked basaltic lava flows and a few dismantled cinder cones, cut by numerous dykes.

Fajãs Norte Grande at the northern shore of São Jorge. (Screenshot of a photo sphere by Marco Gonçalves)

2. The younger western part, with the two main volcanic complexes of Manadas (Pleistocene deposits) and Rosais, dates back to ~0.75 Ma. Rosais Volcanic Complex comprises the NW part of the island; its lavas have a similar composition to those in Topo.

3. Manadas Volcanic Complex on the central southern part is the most recent formation and consists of Strombolian cones and two Surtseyan cones (Morro de Lemos and Morro Velho), as well as craters and tuff rings resulting from phreatomagmatic activity.

ERUPTIONS IN HISTORICAL TIME

(In the following I rely mainly on the translations and interpretations of N. Wallenstein et al., 2018.)

View towards the Bocas de Fogo da Urzelina and other monogenetic volcanic cones on the crest of central São Jorge. This is where the last eruption originated. (© JCNazza, via Wikimedia)

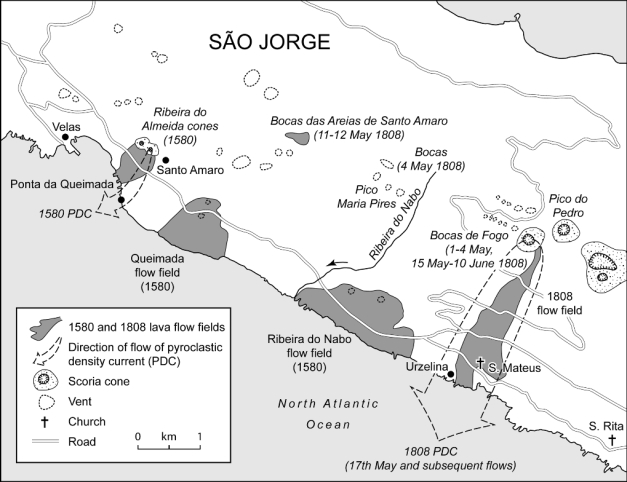

Detailed sketch map of the eruptive activity of 1580 and 1808 eruptions. (From: N. Wallenstein et al., 2018)

Two subaerial eruptions are recorded on São Jorge in historical time: 1580 and 1808. During 1580 basaltic lava issued from three locations above the coastal towns of Queimada and Velas with the flows reaching the sea. This event was the largest, classed as a VEI 3. It lasted four months. Both eruptions not only produced lava flows, they also generated phreatomagmatic activity. Additionally, pyroclastic density currents (PDCs) sweeping down to the sea caused fatalities in both events. Reports of the eruptions and their impacts suggest that the 1580 PDC was a hot flow, whereas the 1808 PDCs were cooler and more moist.

In the years 1757, 1800 and 1902 submarine eruptions were reported on several occasions from vents off the southern and SW coasts. Apparently, each of these lasted just one day.

The 1580 eruption

The priest Gaspar Frutuoso wrote, in his account of the 1580 eruptions, that:

after two days of felt earthquakes the eruption began on 30th April. Two vents opened less than 2 km SE of Velas, above the Ponta da Queimada lava delta. Two scoria cones were formed at the Ribeira do Almeida eruption site. The ash plume was so high that its top was ‘out of sight’. On 1 May, basaltic lava flowed from the cones into the sea. Later that day, more volcanic activity began with the opening of a vent ca. 1.3 km further to the SE among the vineyards near Queimada. The lavas continued to flow for two days into the sea, creating new ‘mysteries’* at the Ponta da Queimada lava delta. – Today the western end of the runway of São Jorge airport is built on this flow field.

Eruptive activity then began further to the east of Velas at Ribeira do Nabo. Continued ash fall prevented people from leaving the church and, after three days, the build-up of ash meant that the doors could only be opened by digging out the tephra.

Follows the apparently first description of a pyroclastic flow: Sometime later, fifteen men returned by boat to collect possessions from a farm building in vineyards that were being threatened by the eruption. Some men stayed in the boat whilst others went into the farm building to collect their possessions. A large cloud then engulfed the house. Some of the men startled by the shadow ran towards the boat followed by the cloud “and the air of the cloud burned all of them, with skin falling from their bodies”. Those who remained in the house were killed and others were severely injured. Parish registers refer to 10 fatalities from the “terrible cloud burning like hell”. – After this disaster limited evacuation from the island was permitted and the eruption lasted for four months.

*Mysteries or mistérios are patches of young, rough and rugged lava terrain. The origin of the name of these geological formations dates back to at least the 16th century. At that time the great eruptions in the islands of São Miguel and São Jorge, forming extensive lava flows, were incomprehensible and mysterious to the early settlers.

The 1808 eruption

Bocas de Fogo da Urzelina, the main cone of the 1808 eruption on São Jorge. (© JCNazza, via Wikimedia)

In 1808 a series of phreatomagmatic explosions and lava eruptions took place from vents along the south-central crest of São Jorge. By pure coincidence this eruption began on the same day as the one in 1580: Following a week of high seismicity, on the night of 30 April 1808, eight earthquakes per hour were felt. Before the sun set, one was so large that it shook the people of Urzelina from their beds.

On 1 May, people who had run out of the church and their homes after a loud bang observed a dark cloud rising to a great height from the ridge above Urzelina. This was followed by a continuous roar from the vents on the ridge. Houses were covered in ash abt. 1 m deep. More vents became active, throwing incandescent bombs of up to 3.78 kg weight over a distance of 1.2 km. The eruption had started in the middle of a lake in a pasture, on a ridge above Urzelina, and had formed a crater of ca. 10 hectares (25 acres). A series of vents developed on the ridge which became known as the Bocas de Fogo. The eruptions caused much destruction and over 30 deaths in Urzelina. Lava flows to the southern coast produced a delta of basalt forming the Ponta da Urzelina.

The eruption declined gradually until it came to an end after 1 month and ten days. It was the last event in the Azores islands that completely originated from sub-areal sources.

Furna das Pombas at Urzelina is the mouth of a lava tube; possibly from the 1808 eruption but it has never been investigated for its origins. It can be explored by small boat for more than 100 m into the interior during low tide and calm sea. Inside it has massive basalt walls and protrusions which are used by large flocks of rock pigeons as nesting place and shelter. (© José Luís Ávila Silveira/Pedro Noronha de Costa)

“HOT” and “COLD” Pyroclastic Density Currents

(PDCs, also often referred to as Pyroclastic Flows or PFs in English or Nuées Ardentes in French)

Interesting here is the notion that the term ‘nuées ardentes’ was actually coined 1580 in the contemporary Portuguese account from São Jorge as ‘nuvem ardente’. The term had only become widely used since the 1902 Mt. Pelée eruption. Scientists had long been wondering why nobody else had described the phenomenon prior to that. But it was first the French geologist F. A. Fouqué who visited the Azores 1873 and translated the term from the Portuguese expression. The geologist Lacroix used it later to describe the ‘glowing clouds’ produced by Mt. Pelée.

The two eruptions on São Jorge were unusual in that PDCs have been generated by these (relatively small) basaltic events at all. This can happen either from phreatomagmatic explosions, from gravitational collapse of scoria cones, or from collapse of lava accumulations at the top of a steep slope. The hotter and incandescent nature of the 1580 PDC and the local topography might suggest collapse of an active lava flow from the top of the scarp. The cooler 1808 PDC is thought to have been a surge of phreatomagmatic origin, according to the statement that it began “in the middle of a lake”.

Looking south down the slope, along the path followed by the PDC on 17 May 1808 from Bocas de Fogo to Urzelina. (From: N. Wallenstein et al., 2018)

On 17 May (1808), while working to save some valuables from the church, the priest saw a huge flame that rose from the volcano. A medonha e ardente nuvem [fearsome burning cloud] came down the slopes, setting fire to the vineyards, bushes and trees and burning around 30 people as it approached the church. Another note states that the nuvem ardente was a humid dust. Most of the inhabitants fled; some, however, remained in the vicinity too long, endeavouring to save their furniture and [other] effects, and were scalded by flashes of steam which, without injuring their clothes, took off not only their skin, but also their flesh. About sixty persons were thus miserably scalded, some of whom died on the spot or a few days after.

It was later argued, on the grounds of missing incandescence and the moist nature of the ash, that the 1808 flow was cooler than that of 1580. It was not hot enough to burn clothes, but in places was still hot enough to flash water to steam. So it would scald victims and asphyxiate them as they inhaled the piping hot gases.

THE CENTURY-OLD QUESTION: WILL IT ERUPT AGAIN?

As with Pico, Faial and the other Azorean islands there is no telling if at all, and when. The archipelago sits atop a very active spreading zone and thus the ilha de São Jorge can become affected by all sorts of geological events. The most obvious reminder are the frequent earthquakes which accompany all of them. They occur when a fault is widening or when parts of the ocean crust are rising or sinking. They also occur when magma is rising from deeper down producing submarine eruptions or – on land. If it should happen on São Jorge again, it may not erupt from the same craters as before, as these are all monogenetic cones. Meaning they do not have an established plumbing system underneath connecting to a magma source. If the rift becomes active again, it may open up new vents anywhere. But again, this is a long process with many tell-tale signs in advance. Volcanologists have an eye on their instruments and will give ample notice of any unusual observations.

The Town of URZELINA

The lovely town of Urzelina, with its lava flows and tube at the shore and its lonely bell tower (church ruined in the 1808 eruption) at the edge of the forest. (© azoreseasycamp.com/english/campsites-guide/)

The old church tower of Urzelina. In 1808, a lava flow from the erupting volcano above ruined the church, just the tower remained. Today it is the landmark of São Jorge. The trees in the background hide the front of the old lava flow. (© Angrense, via Wikipedia)

About 10 km SE of Velas, past the airport, lies Urzelina with a charming little centre and some beautiful small bays that made it the island’s most popular bathing venue during the summer months. Its history has certainly been shaped by the eruption of 1808, which destroyed a great part of the settlement, and caused fear and panic in its residents. It also resulted in the destruction of most of the arable lands around it (and plunged the entire island into a period of famine). Lava had also reached the local Church of São Mateus, which was inundated and ruined by the basaltic flows. Only the Torre da Antiga Igreja de Sao Mateus (the old bell-tower and belfry) stands as stark reminder of the disaster.

The town and parish were named for the abundance of urzela (Roccella tinctoria) found and used by the first explorers and settlers. Urzela, a species of lichens, could be used for dyeing yarns in a natural red-violet colour. It was ground between millstones for the process and made into a tincture. Later its chemical components were used as an acid-base indicator such as litmus. So it was an important source of income for the islanders and even became an export article sold to Flanders and England in the early 15th-16th centuries.

~~~

BESIDES…

Among the traditional and exclusive dishes of the island of São Jorge there are those that are made with clams – this is the only island in the Azores where this species is found. The clams live only on the banks of a lagoon in the Fajã da Caldeira de Santo Cristo, on the northern coast. They are protected, and only certified people may collect them for the local cuisine. Nobody seems to know how the clams got there, and why they reproduce so easily in this particular place.

Another speciality is the island cheese. Although cereals, vines and local vegetables are still grown on small patches, farmers on São Jorge are currently betting on the dairy industry. Delicious local São Jorge cheese has now become the most important part of the local economy.

Left: Cheese wheels – the new economy… (© Luis Miguens, via theazoresislands.blogspot.com) Right: Delicious clams of São Jorge. (© ‘Restaurante Bar Cais 20’ on FB)

Some traditions of the island’s Catholic communities have their origins in catastrophes associated with historical earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. An example are the Romeiros (pilgrimages) where groups of people go on a walk from their home village around their entire island. They stop on chapels or stations to pray and reflect, stay overnights and proceed the next day.

~~~

Western part of São Jorge, looking east. It seems that the tops of the old volcanoes on both ends of the island have been eroded away. This part at least is almost absolutely flat. (Screenshot from video by Lion Manuel on YT)

Fajãs Norte Grande at the northern shore of São Jorge. Fajãs: Although in several descriptions made for tourists I read that these flat coastal places are created by the deposits of landslides long ago, one can see in photos that many of them are actually deltas of lava that once flowed into the sea – just like presently happening in Hawaii. (Screenshot of a photo sphere by Marco Gonçalves)

Paradise in Black Lava… natural Pool of Simão Dias, Fajã do Ouvidor, on the northern coast of São Jorge. (© Rui Vieira, via Rui Vieira Photography)

Morro Norte (Velas) on the south coast. An ancient surtseyan cone with a base of very old basaltic lava. This was later covered by various layers of palagonitic tuffs from more submarine eruptions. (© JCNazza, via Wikimedia)

Ponta dos Rosais seen from the sea, westernmost point of São Jorge island. (© Fcardigos, via Wikimedia)

~~~

Disclaimer: I am not a scientist, all information in this (and any of my other posts) is gleaned from the www and/or from books I have read, so hopefully from people who do get things right! 🙂 If you find something not quite right, or if you can add some more interesting stuff, please leave a comment.

Enjoy! – GRANYIA

SOURCES & FURTHER READING

– GVP, São Jorge

– […] the 1580 and 1808 eruptions on São Jorge Island (2018, paywalled)

– Active tectonics and first paleoseismological […] and S. Jorge islands (2003, download)

– Bocas de Fogo (Wikipedia)

– Magma flow pattern in dykes of the Azores (PDF, 2014)

– Jessie On a Journey (blog)

– Active tectonics in the central and eastern Azores islands […] (2015, paywalled)

Our previous Azores posts:

– 1-São Miguel – 3-Terceira – 4-Faial – 5-Pico – 2-Geology

This week international scientists made an unexpected discovery near the Azores with the Portuguese ROV “Luso”: Hydrothermal chimneys on Gigante Seamount, ~100 km from Faial island towards the Mid-Atlantic Rift, at 570 m depth.

https://phys.org/news/2018-06-extraordinary-hydrothermal-vent-discovery-mid-atlantic.html

LikeLike

Kilauea summit earthquake ciycles in June so far. Average recurrence time for the daily large quake (~M5) is 24.84 hours (24 hours and 51 minutes).

LikeLike

USGS tweet: “GPS station NPIT at Kilauea is no longer able to transmit data after subsiding 310 feet (95 meters), but two new stations have been installed on the caldera floor – CALS and VO46. Check out the real-time data plots for these stations at https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/volcanoes/kilauea/monitoring_deformation.html“.

LikeLike

You know, that 24h 51′ change in large earthquake is very close to the tidal timing. Tides lag a bit and take around 12h 25′ for a single cycle. Interesting coincidence? Cheers –

LikeLike

Yes, I had thought of this too; it sure looks weird. But, if you look at the plot, you see that the time spans have decreased over time. If they decrease further (or increase again) that average will change. And, thinking logically, a strong EQ occurs when enough internal gas pressure has built up from the degassing magma to break through the blocked surface. I believe it would make no sense to connect it to tides. You never know, though; this eruption will bring about a wealth of new research results, I look forward to seeing the ones about the EQ cycles.

LikeLike

Sierra Negra volcano, Isla Isabela, Galápagos: IGEPN Special Rep. No. 7: New swarm of earthquakes began. Depths vary between 3 & 5 km and max. magnitude was 4.6. Although IGEPN say it “could be the precursor of an eruption”, they may not declare an eruption before someone had actually seen it erupt. To my squinting eyes it looks like an eruption has already started… 😉 could be wrong, though.

https://www.igepn.edu.ec/servicios/noticias/1596-informe-especial-volcan-sierra-negra-n-7-2018

Edit:

Reports state that people begun to hear noise from the volcano after an EQ at 13:40 GT. The above seismogram ends at 13:05 GT. So, unless the eruption started quietly, what we see is not the beginning of it. Therefor my squinting eye was wrong. 🙂

LikeLike

LikeLike

From PhysOrg, an article about Laguna del Maule straddling the Argentine – Chile border. Cheers –

https://phys.org/news/2018-06-bathtub-giant-volcano-field-movement.html

LikeLike

Nice one again. Did not know there has been such PF there.

some insight on the local seismicity since 1980

LikeLiked by 1 person

Something interesting happening on the lower right hand corner of the plot? Lots of earthquakes centered around there 38 30′ – 38 00′ and 27 00′ – 26 30′. Need to review how the islands grew (west to east? / north to south? / something else?). Cheers –

LikeLike

The MAR is in the west, so the oldest islands are E. But we know this area IS active. S. Miguel is ~150 km SE of the quakes and it has active volcanoes. You’d have to look up a fault map. The main rifts and faults go NW-SE. Find one that cuts in an angle, and if the quakes are where the two faults cross there might be volcanic action. If there are no crossing faults near, they’re probably just the usual rifting events.

LikeLike

You know, I think it’s at or near the Castro Bank. Has not one of the VC guys written a post about that as a place to watch out for?

LikeLike

Which would make it about a third of the way SE along the main rift from Terciera to Sao Miguel. I did a post on Azores tectonics. Completely missed the Castro Bank, though. Looks like generally, the farther east you get, the older the island. The closer you get to the MAR the younger. For some reason, seismicity since 1900 does not necessarily correspond with island age or volcanic activity. Lots of quakes along the North Azores Fracture Zone as it approaches the junction with the East Azores Fracture Zone. Something interesting is clearly going on. Cheers –

LikeLike

New post is up! 🙂

LikeLike